As coordinator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch, an initiative that analyzes satellite data to measure heat stress on coral reefs, marine scientist Mark Eakin watched an unprecedented three-year global bleaching crisis begin to unfold in 2014. To read Eakin and his coauthors’ recently published chronology of those years is to feel like you’ve stumbled into a dystopian science fiction novel about a fatal pandemic as it slowly dawns on the protagonist just how dire the situation is and how far and fast it’s spreading.

“CRW satellite monitoring first detected heat stress sufficient to cause coral bleaching in Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.”

“Papua New Guinea and Fiji reported moderate heat stress and bleaching early in 2015; American Samoa reported its worst bleaching ever.”

“Hawaii saw its worst bleaching ever. Florida’s reefs experienced a second consecutive mass bleaching. …”

“The first mass bleaching (85 percent bleached) of the northern and far-northern Great Barrier Reef killed 29 percent of the GBR’s shallow-water corals.”

Climate change from the burning of fossil fuels has steadily raised ocean temperatures. But from 2014 to 2017, big spikes in ocean heat levels stressed the world’s coral reefs before temperatures finally fell and an intense El Niño weather pattern ended. During that time, corals in the world’s tropical oceans bleached en masse – expelling the symbiotic algae that provide them with color and nutrition. If temperatures cool, coral polyps can recover. But as the heat persisted, untold hundreds of millions of corals died, documented in a drumbeat of depressing dispatches from the South Pacific accompanied by images of widespread destruction.

“I tried to alert people when satellites showed how bad it was getting,” said Eakin. “There were those horrible days when I would start getting reports emailed in with photos showing how bad it was, and my heart would just sink.”

The worldwide bleaching episode is now considered the longest and most destructive of the three that have occurred since 1998. NOAA estimates that three-quarters of global reefs hit the first “alert 1” level of heat stress, where bleaching is a major risk, while nearly a third suffered “alert 2” levels of heat that are likely to kill them. Half the corals on the 2,300km-long (1,400 mile-long) Great Barrier Reef – about a billion of them – were bleached to death between 2015 and 2017.

NOAA Coral Reef Watch’s satellite coral bleaching alert area shows the maximum heat stress during the 2014–2017 bleaching events. Regions that experienced the high heat stress that can cause coral bleaching are displayed. (NOAA Coral Reef Watch)

Now the Coral Reef Watch program is taking a step back and asking a difficult question: What was the actual extent of the damage to crucial ocean ecosystems that provide habitat for a quarter of the world’s marine species and provide food and livelihoods to hundreds of millions of people? Although there is data on bleaching events scattered across the world, there’s no easy measure of the global toll of the crisis.

Corals generally bleach once temperatures cross a given threshold, but that line varies by species, local ocean currents and other conditions. Whether corals actually die or bounce back is also highly variable.

Bleached coral in American Samoa in 2015. (THE OCEAN AGENCY / XL CATLIN SEAVIEW SURVEY)

In many cases, this kind of data isn’t easy to come by, especially in regions not as heavily monitored as places like Florida, Hawaii or the iconic Great Barrier Reef – and even in the latter, it’s impossible to conduct comprehensive surveillance given its size. The Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, a scientific collaboration that for more than a decade systematically compiled data on global reef health and bleaching, shifted to a more regional focus after 2009 as its organizational priorities changed, Eakin said.

Eakin and NOAA ecologist Denise Devotta have now taken up the challenge. After six months of outreach and diplomatically persuading other scientists to share their data, they have obtained around 13,000 observations on the health of corals – whether or not they had bleached and how much – between 2014 and 2017 from more than 80 countries. Devotta is now working on the gargantuan task of trying to standardize the data so they can conduct a global analysis.

While the analysis of all that data is just getting off the ground now, Eakin hasn’t seen any big surprises yet. But the details will matter. It will be the first big global test of how accurately NOAA’s coral bleaching warning and forecasting system – which tried to give advance notice of coming devastation – performed.

For the last decade, NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch has offered tools that show coral bleaching risk based on satellite data of sea surface temperatures. Around 2010 – at the time of the last global bleaching event – it began drawing on climate models to make longer-term predictions. Two years later, Coral Reef Watch could issue bleaching alerts four months in advance. “By the time we got to 2014, enough of the community had been using [the forecasts] and people were really paying attention, saying this is a forecast we can trust to make decisions,” said Eakin.

Eakin hopes to test and improve upon whether those forecasts matched up to the reality under water. Of course, better forecasts aren’t going to save corals from climate change. But they could help officials take steps to reduce other stresses on coral reefs, such as tourism and fishing, while ramping up monitoring efforts. Thailand, for instance, shut down tourism on certain reefs in 2016 to help them withstand and recover from bleaching stress.

David Gulko, who runs the state of Hawaii’s Coral Restoration Nursery, was able to make use of advance warning in 2015 after Eakin contacted his office about a high risk of bleaching headed their way. Initially he was skeptical, as usually Hawaii’s corals are relatively protected from heat stress by the cool deep waters that upwell in the islands.

“When [Eakin] came out and said, ‘Hey, this is very different than what we’ve seen in the past,’ we talked, and based on talking with him, I became convinced that we were going to be seeing some bleaching,” said Gulko.

Before that happened, Gulko organized a team to collect samples of rare species of coral endemic to Hawaii – sometimes only found in one bay – to build an “ark” of corals to be preserved in the nursery – an insurance policy in case their wild brethren didn’t survive the heat that summer.

It turned out at least one species – the Hawaiian knobby coral – did appear to die off. “When we went back after the bleaching event, those colonies were dead and gone,” he said. After growing the collected fragments in the nursery, Gulko is planning to reintroduce them into the wild this year. (A tide pool where they sampled another rare coral was also recently destroyed by lava from the Big Island’s erupting volcano).

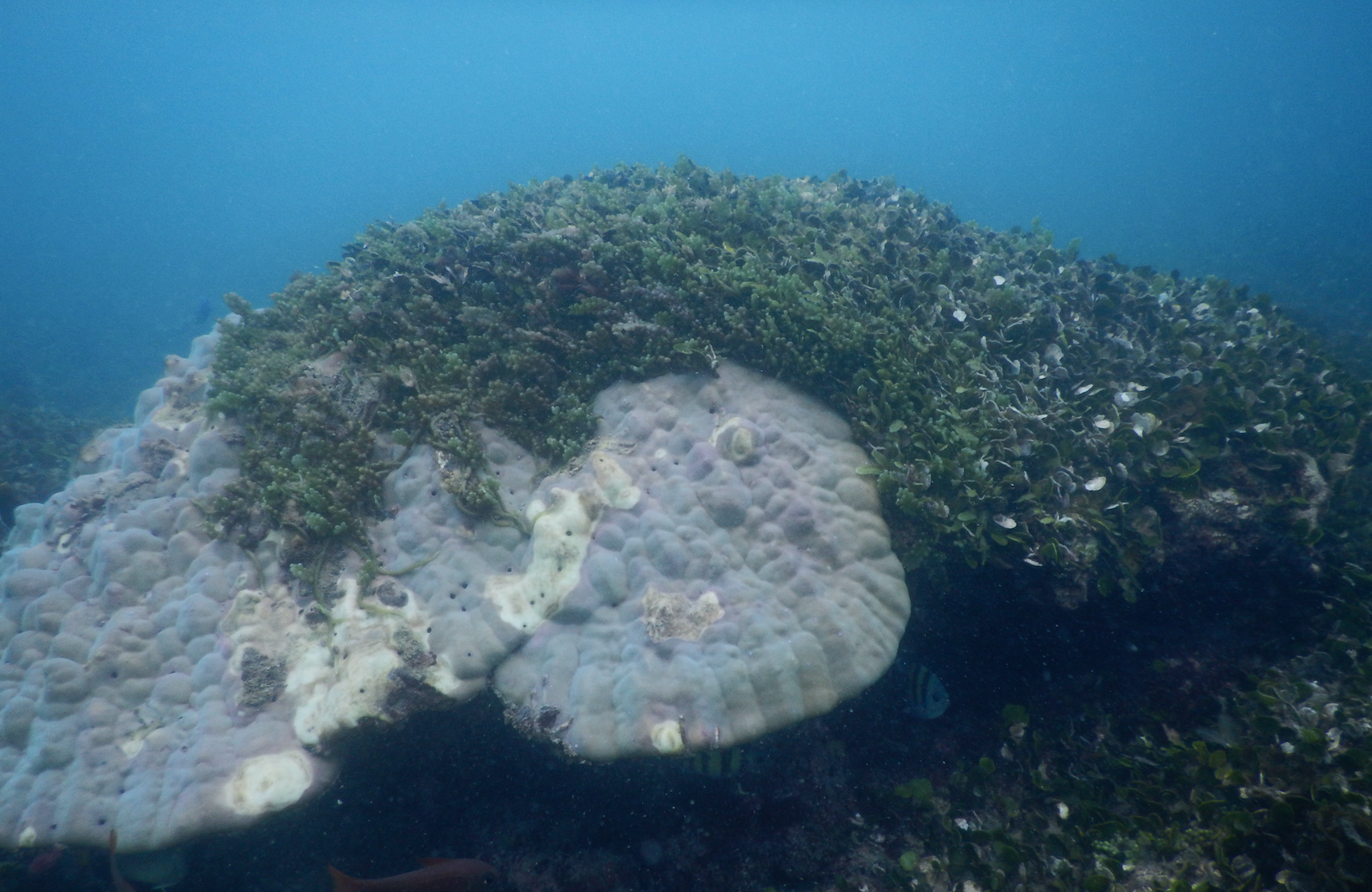

Macroalgae taking over bleached corals in the Gulf of Mannar, India, in February 2018. (Courtesy of Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute)

K. Diraviya Raj, an assistant professor at the Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute in southern India, became aware of NOAA’s forecasts after being contacted on Facebook by Eakin for records of bleaching in the Gulf of Mannar. Although corals in the Gulf bleach every summer, they usually recover. In 2016, however, it was too hot for too long and Raj estimates that about 16 percent died. In some areas, macroalgae are now smothering dead reefs, making it hard for new coral larvae to recolonize the area, he said.

His institute is working to prepare a rapid response plan for future bleaching episodes in India, and he said the Coral Reef Watch forecasts will be helpful to resource managers. India has three other coral regions, but the others are far less monitored by scientists, he said. “We are trying to tell them what is coral, why is it important and why we need to conserve it; and we are trying to get volunteers in every region to report bleaching so we can do the surveys and act immediately.”

Raj was saddened when he watched the 2017 Netflix documentary “Chasing Coral,” which documented global coral bleaching, and saw that India wasn’t included in a map of bleaching, he said. That’s one reason he was eager to contribute data to NOAA’s data-collecting effort.

“I want India to be on that map,” he said. “We have corals, and there are people who are actually concerned for corals and want to conserve them.”

This year, it appears reefs will get a respite from marine heatwaves. But scientists say it’s only a matter of time before the next bleaching event strikes.

“The climate models are not forecasting anything too severe this year,” said Eakin. “We’re not expecting a really bad year, and we’re certainly not expecting another global event. I’m thrilled by that.”